The Larger-Than-Life Phenomenon of Oregon's Pendleton Round-Up

As they say at this time-honored rodeo, let ‘er buck.

The name Ken Kesey brings up quite a few things that, shall we say, push people’s boundaries: LSD and other psychedelics (occasionally involving the CIA), the Merry Pranksters traveling the country in a far-out school bus (as chronicled in Tom Wolfe’s Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test), and the madness of mid-century institutionalization in the Oregon author’s most famous release, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. But for his final novel, Last Go Round, Kesey delved into somewhat of a more mainstream affair, tracking down a particular story that had been following him for decades.

Since the age of 14, Kesey had been captivated by something that happened at one of the first Pendleton Round-Ups, a major rodeo that’s been drawing thousands of spectators and competitors to rural Oregon every year for more than a century. He heard about it from his father, Fred Kesey, on a hunting trip to the Ochocos. After a long day that included a travel delay due to Round-Up-related traffic, the younger Kesey and his brother gathered around the campfire for a story.

...after the judges deemed Spain the winner, the crowd protested by loudly cheering for the losing Fletcher

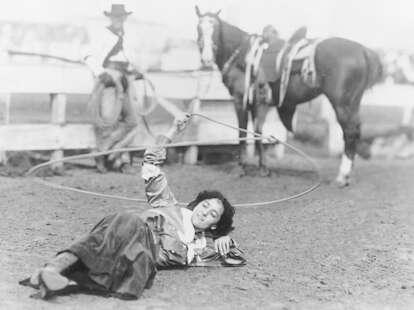

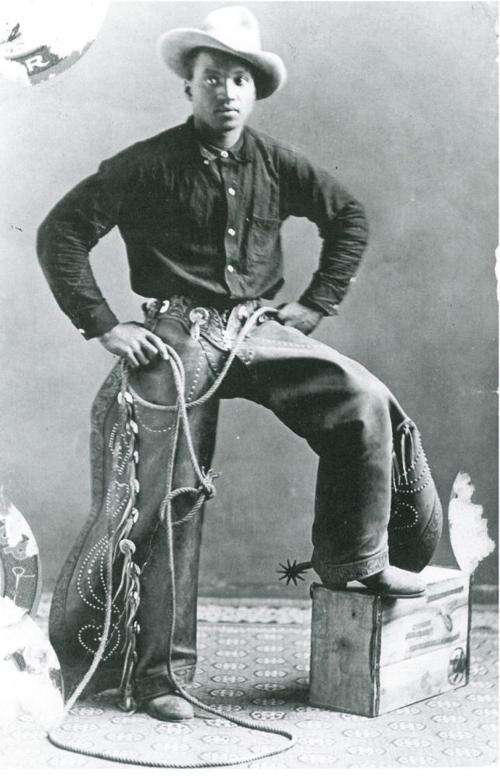

As Fred told it, the 1911 Pendleton’s saddle bronc championship came down to George Fletcher, a Kansas-born Black man raised by his mother on the Umatilla Reservation; Jackson Sundown, a member of the Nez Perce Tribe and a nephew of legendary leader Chief Joseph; and John Spain, a white rider from a small town near Eugene. Controversy erupted when, after the judges deemed Spain the winner, the crowd protested by loudly cheering for the losing Fletcher and dubbing him the people's champion. To appease the masses, then-Umatilla County Sheriff Tillman Taylor took Fletcher's hat, tore it into pieces, and sold it off bit by bit, providing Fletcher the funds to purchase a saddle just as good as Spain's.

The sheer diversity among the story’s players grabbed Kesey right off. Here were three cowboys—one Black, one white, and one Native American—all sharing equal ground way back in 1911. The resulting book, Last Go Round, was published in 1994 and portrayed Spain, Fletcher, and Sundown engaging a fictionalized reenactment. (It also featured, for some reason, Western icons like Buffalo Bill and tribal preacher Parson Montanic, who weren’t actually there.)

What young Kesey perhaps didn’t know at the time was that, though it might not be obvious today, rodeo’s roots are anything but homogenous. In fact, cattle herding itself can be traced back to North Africa, where Spanish colonizers first observed the practice before bringing it with them to North America. They also brought along their own form of rodeo, called charrería, and it was the Mexican vaquero that eventually taught Anglo ranch hands their ranching skills. During the post-Civil War Open Range Era, a quarter or more of the cowboys involved were African American, Mexican, or Native American. In fact, the word “cowboy” in antebellum Texas was racially derogatory—white cattle workers were cowhands, while Black ranchers were pejoratively referred to as “cowboys.”

As is human nature, finely tuned ranching skills eventually became fodder for competitions, and soon the modern rodeo was born. Today, in addition to the massive professional rodeos held throughout the United States and Canada, there are also smaller Black rodeos and Native American rodeos, both of which are growing fast in popularity.

Last Go Round isn’t a particularly good read, especially considering Kesey’s oeuvre, but it stands as a testament to the Round-Up’s strong community ties as well as Fletcher’s enduring legacy. In 1969, the celebrated rider was among the first to be inducted into the Pendleton Happy Canyon Hall of Fame, and in 2001, he made it into the National Cowboy Hall of Fame. A statue of Fletcher popped up on Pendleton’s Main Street in 2018, with a prominent mural following three years later. Though if you asked him, he wasn’t any sort of Civil Rights pioneer. He was just a cowboy.

Beyond Fletcher’s impact, the book shows that since that early event, the Pendleton Round-Up has always been a larger than life phenomenon with a profound and lasting cultural impact.

In the early 19th century, what is now the city of Pendleton, Oregon was merely a wide open space that served as one of many stops along the Oregon Trail. In 1851, a trading post was established at the confluence of McKay Creek and the Umatilla River by one Dr. William C. McKay, giving folks more reasons to pass through the small Western patch.

A decade later, the area caught the eye of Moses Goodwin and his family, who stopped on their way to Idaho, looked around, and decided that they’d like to stay awhile. Goodwin traded some of his mules to a squatter for 160 acres of land and established Goodwin Station, and later, Goodwin’s Hotel. In 1868, he and his family deeded 2.5 acres of land to Umatilla County to make a town. For reasons that remain unknown (at least to us), they named it after Ohio senator and 1864 vice presidential candidate, George H. Pendleton.

It goes without saying, of course, that this land was not really theirs to give. In the 19th century, Manifest Destiny in all its land-grabbing forms was promoted by the local government, specifically Washington Territory Governor Isaac Stevens, at the intentional expense of the area’s Indigenous peoples. The subsequent city of Pendleton was built on a portion of Pacific Northwest land once home to the Umatilla, Cayuse, and Walla Walla people. Leading up to the city’s founding, in 1855, after two weeks of negotiations and, to be frank, with no other viable choice, tribal representatives agreed to cede 60,000 square miles to the government of the soon-to-be state of Oregon in what was known as the Treaty of Walla Walla. In return, they walked away with the Yakama Reservation in Washington, the Umatilla Reservation in Oregon, and the Nez Perce Reservation in Idaho, while the rest of the land remained open to white settlers. The five displaced tribes from the Eastern Oregon and Washington Territories later came together to create the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation, still located just outside of Pendleton.

By 1910, Pendleton was fully incorporated, and an enterprising young local businessman decided it was time to introduce this new town to the world. After a Fourth of July event showcasing feats of horsemanship was met with great success, he proposed a rodeo celebrating the end of harvest, a spectacle intended to draw crowds from all around the region and a chance for the farmers to unwind. And so, in September of that year, the Pendleton Round-Up came to be, and with it the slogan, “Let 'er Buck.” This year’s rodeo takes place from September 9 to 16.

Now, as back then, it’s a community endeavor: The organization’s 17 directors all work as volunteers. And from the beginning, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation has been an integral partner in the festivities. At that first Round-Up back in 1910, the Confederated Tribes set up an encampment of tents next to the arena grounds and gave demonstrations of traditional dances and horsemanship as well as beadwork, leatherwork, weaving, and basket making. Today, tribe representatives do much of the same, with a whopping 300 tribes represented throughout the event.

Attendance has grown from 7,000 in 1910 to some 50,000 in 2022, all of whom descend upon the grounds each year to expand the town’s population from 17,000 to 70,000. The rodeo even has its own signature booze, by way of Pendleton Whisky. And though rodeo season may be winding down for the year, if there’s one to hit, this is it. “The Round-Up is probably one of the most well known and understood events in the Northwest rodeo industry,” says Pat Reay, the Round-Up’s publicity director—and its got the numbers to prove it. “Every play field, baseball field, and vacant lot has a camper or an RV.”

It’s a full-on celebration of Western community and culture. There are Western and Native American parades alongside the Happy Canyon stage, home to concerts, pageants, Western and Native American shows, and, perhaps most notably, a kickoff concert headlined by superstars Craig Morgan and Clint Black.

This year, there are 820 rodeo contestant entries, an all-time high. And you’re going to see some true talent. “Most of the top contestants are going to be here because they're trying to win money towards the end of the season, and also qualify for the National Finals Rodeo,” says Reay, referring to Las Vegas’ high stakes December showdown. The riders also come for Pendleton’s one-of-a-kind facilities. “We have a grass infield which is totally unique to a rodeo arena,” says Reay. “Most of them are dirt.”

Things can get wild—it’s the nature of the beast. And you may also smell cow patties—the literal nature of the beast. Both human athletes and animal athletes have trained for this their whole lives. But whether or not you agree with the rodeo’s M.O. is another matter. Rodeoing’s history has not been without controversy. Opponents say that the animals—including baby calves—have sustained cruel injuries, suffering broken bones, ripped tales, and other bodily harm. What began as a showcase of everyday ranching skills has, they say, been exploited for financial and entertainment purposes.

Yet it should also be acknowledged that rodeos, especially ones as long-running and prominent as Pendleton’s, are often about much more than bucking broncos and wrestling steers. The deeply rooted relationship between the rodeo community and the town’s very identity are on full display at Pendleton’s Round-Up’s Hall of Fame, a sentiment that echoes around the quaint downtown area like an Old West relic frozen in time. That’s where you’ll find the Tamástslikt Cultural Institute, an immersive exhibit telling the story of Westward Expansion from an Indigenous point of view, while the Heritage Station Museum documents the path of the pioneers.

If it’s going to be your first rodeo, there really is no better place to get your cowboy boot-clad feet good and wet. Here are some tips to help you make the most of it.

Wear comfortable clothing

The short answer to what to wear? Whatever’s comfortable. The long answer: Go wild. It’s expected, and you’ll look silly otherwise. That shirt with the beaded silver tassels you’ve been eying? Now’s the time. Pick out some boot scootin’ boogie cowboy boots, grab a bandanna or bolo tie, and go big on accessories. (For a fun preamble, hit up the PBR tour—a.k.a. Professional Bull Riders—at New York City’s Madison Square Garden to see decidedly non-cowboys try to one-up each other with the size of their belt buckles.)

Up in Oregon, however, rodeo is a way of life, from county fairs to college and high school events. Rest assured that if you have nothing to wear, you can purchase it on premises. Jeans and a T-shirt or a button-down will do just fine, but hey, when in cowboy country…

Familiarize yourself with the lineup

At its core, professional rodeo is a competition based on everyday skills still used throughout the ranching industry. “Each event has something unique that showcases the Western way of life,” says Reay.

Contests are divided into two categories: roughstock events and timed events. In the roughstock events—bareback riding, saddle bronc riding, and bull riding—both the animal and the rider receive scores up to 25 points by two different judges, with the hopes of getting a perfect 100. In timed events—steer wrestling, team roping, tie-down roping, and barrel racing—contestants are competing against the clock as well as against each other. “The fastest time is going to be your leader,” says Reay. “This may be the easiest to understand for a first-timer.”

Regardless of the event, they’re all vying for a ticket to the National Finals Rodeo in Las Vegas.

And then there’s wild cow milking, where cows not used to being milked are roped and milked by a team. In other words: udder chaos.

Immerse yourself in Native American culture

The Pendleton Round-Up is as much a showcase of Native American culture as it is ranching culture, and there’s evidence these tribes have inhabited this region for more than 11,000 years. Next to the grounds, members of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation—the Umatilla, Cayuse, and Walla Walla peoples living eight miles east of Pendleton—host a Grand Tribal Village. There, participants travel from miles around to oversee more than 300 teepees.

Partners with the Round-Up since its inception, you’ll find tribal representation in rodeo matinees as well as the Happy Canyon Pageant. There are also two tribal beauty contests—the American Indian Beauty Contest and the Junior Indian Beauty Contest. There’s also a Round-Up Pow Wow dance competition along with vendors selling Native American handicrafts. And if you get hungry, you can snack on traditional food like fry bread. (Who are we kidding—you don’t have to be hungry to go for some fry bread.)